Amonth after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s state visit to the US in June 2023—when semiconductor major Micron announced plans to invest in India—he inaugurated the second edition of the annual Semicon India summit in Gandhinagar, Gujarat.

Read More: TCS employees’ hikes, variable pay now depend on their return to office

Since it came close on the heels of Micron’s announcement of its intention to set up an ATMP (assembly, testing, marking, and packaging) unit, there were hopes that more would follow. There was just one; AMD’s commitment to invest $400 million to set up its largest design centre in Bengaluru. But India has yet to receive an application from a leading chip player for setting up a semiconductor fabrication unit. Media reports suggest that Tower Semiconductor has filed a fresh application, but the government is yet to confirm this.

Of course, India’s dream of becoming a semiconductor hub isn’t new. There have been failures aplenty over the past 60 years. But hopes soared that that script would change when, in December 2021, the government announced a production-linked incentive scheme worth Rs 76,000 crore for chip and display fabrication units.

The timing seemed ideal since the announcement came in the middle of an acute shortage of chips globally. Timing apart, the government is aware of the challenges in this path and is taking the long view. Rajeev Chandrasekhar, Minister of State, Ministry of Electronics and IT (MeitY), says, “Semiconductor manufacturing is not a today or tomorrow game. It is a day after tomorrow and down the road game… decades-long game.”

The trouble is that other countries too saw this as a chance to bring chip production onto their shores. From the US to Europe, Japan, and even developing nations like Malaysia, a host of countries are attracting investments.

This poses a big challenge for India. That’s because setting up a foundry is an expensive affair, costing anywhere between $2 billion and $20 billion, per industry estimates, and it takes six to eight years to break even. Besides, there are a whole host of factors that companies look at before zeroing in on a location. Helen Chiang, Country Manager for IDC Taiwan and IDC’s Lead for Asia Semiconductor Research, highlights four key focus areas: infrastructure (including reliable power, water resources, transportation networks, and telecommunications); a skilled talent pool (in engineering, materials science, and electronics); proximity to major clients, supply chains, and target markets; lead times and shipping risks; and lastly, geopolitical stability. India’s nascent chip ecosystem has some distance to go to meet these demands.

Baggage of the past

The government may have sought a fresh start in December 2021. But it had to first deal with the considerable baggage of the past. India has not just lost out to developed nations but even to developing ones. For instance, Intel has picked Malaysia to build its largest 3D chip packaging facility.

It wasn’t always like this. Way back in the 1960s and ’70s, Intel had shown interest in starting a manufacturing unit in India, but that interest was not reciprocated. “Robert Noyce, the Co-founder of Intel, had visited India in 1969 to explore the opportunity to set up a semiconductor manufacturing facility here. Unfortunately, the government told him that he could only set up a fab that would not exceed hundreds of thousands of chips, which was a complete non-starter. I have often wondered how the tides with Taiwan and China may have turned had we allowed Intel to set up a fab in India back then!” says Vinod Dham, the father of the Pentium processor. It attempted to do so again with a packaging unit in 2005, but without success. That baggage is troubling now. None of the big chip companies, except for Tower, are considering India.

“India missed the bus for 30-40 years, and an impression was built that we could never do it. India can do it, but is struggling to shrug off the image of having failed in the past and is unable to get to the ‘proven ground’ tag,” says independent analyst Arun Mampazhy.

Experts and MeitY officials believe that once the ecosystem is set up—which the government is hopeful will happen with Micron’s ATMP plant that is being set up at an estimated cost of $2.7 billion—the floodgates will open.

But ATMP does not involve manufacturing—it is just the testing and packaging part. That comes towards the end of the chain and is preceded by the design and development part and fabrication.

Building those two aspects is easier said than done.

Talent Crunch

One big hurdle is the dearth of skilled workers. It’s a problem that chip companies are grappling with the world over, and even with its engineering base, India lags on this parameter. “Many semiconductor integrated device manufacturer (IDM) /foundry /ATP/ OSAT (outsourced semiconductor assembly and test) players have provided consistent feedback regarding manufacturing and packaging talent unavailability in India as one of the reasons holding back investments,” says Danish Faruqui, CEO of Fab Economics, a US-based semiconductor value chain economics consultancy. This puts India’s public and private investment in semiconductors at risk of underutilisation.

Quoting a report by the India Brand Equity Foundation, Aditya Joshi—CEO of semiconductor technology, talent, and process solutions firm OpalForce—says India houses over 200 chip design and embedded software companies. However, it currently has a small pool of skilled workers.

Acknowledging this challenge, the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) launched a BTech Electronics VLSI Design & Technology and a Diploma in IC Manufacturing. VLSI stands for very large-scale integration design, and IC stands for integrated circuits. Many colleges have already rolled out the courses, including the premier Indian Institutes of Technology. MeitY aims to create a skilled workforce of more than 85,000 by 2027.

Technology trouble

The applications filed with the Indian government to set up foundries must include a technology partner. Unlike in the past, where governments approved projects with deep financial backing, the current administration has made having manufacturing-grade technology (MGT) as a key qualifier. This has proven a big challenge.

There are very few MGT companies worldwide, like Intel, Samsung Electronics, Micron, STMicroelectronics, TSMC, Tower Semiconductor, and PSMC. The failure to get a technology partner was also the reason the Vedanta-Foxconn joint venture application filed in February 2022 was held up, and eventually that was the reason the JV fell through.

The technology transfer involved takes years. At the moment, no MGT major is interested in engaging in a multi-year saga of technology transfer to entities lacking adequate capabilities for enabling the transfer, adds Faruqui of Fab Economics.

“There are only six or seven companies that have MGT, and all of them have their hands full. They are willing to license but it’s not simply about paper. It is about a group of 100 engineers that have to come [and] license technology to transfer it,” explains Chandrasekhar.

Greenfield Set-up

After Covid-19 and during the acute phase of chip shortage, almost all large countries decided that semiconductor technology and manufacturing were the key strategic and economic assets. They launched schemes to attract semiconductor firms, like with the US’s CHIPS Act. Since developed countries already had an existing ecosystem, large projects with advanced technologies went there.

The Indian government is not unaware of this dynamic. “The US has been [making] semiconductors for decades, since I was a child. They have a mature semiconductor ecosystem, and the US CHIPS Act was simply about incentivising their expansion,” says Chandrasekhar.

But there are many other factors at play as well. Though the government is offering incentives, some industry experts say the infrastructure and operational costs for setting up a semiconductor fab in India are significantly higher than other potential locations like China and Taiwan. “This is due to the lack of a robust electronic components and semiconductor manufacturing ecosystem in India, which leads to dependence on imports for raw materials, equipment, and tools. Moreover, the cost of power, water, and transportation is high in India. Additionally, the cost of land acquisition and environmental clearance can delay the project implementation and increase capital expenditure,” explains Sanjay Gupta, Chairman of the India Electronic and Semiconductor Association (IESA).

Industry veteran and VLSI Society president Satya Gupta, who visited the US recently to meet leaders from across the value chain, says, “Political stability, and more importantly, policy stability and longevity in case there is a political change, was one of the most important doubts in people’s minds. The political, bureaucratic, and technical leadership have to create a better awareness of India’s resolve to create a long-term sustainable and commercially viable semiconductor ecosystem in India and provide assurances that political leadership changes will not affect the policies and incentives.”

Another factor is the availability of raw materials. Access to electronic components is a big challenge. “We are heavily dependent on imports for raw materials, which adds to transport costs, inventory management, and logistics,” says Sanjeev Keskar, Executive Director at EPIC (Electronics Products Innovation Consortium) and former president of IESA.

Scaling demand

Countries like the US, Europe, and Japan enjoy one other advantage: the significant presence of fabless and electronics product companies, which are the customers of chip makers. This makes it easier for chip manufacturers to expand operations and build new fabs.

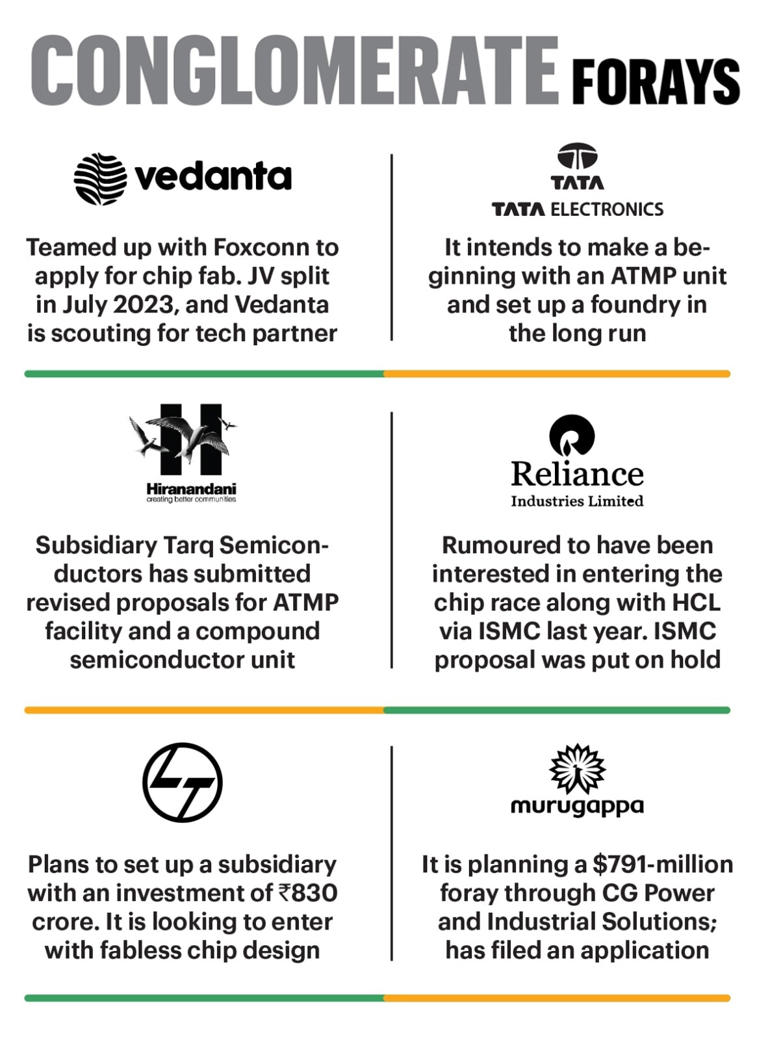

Given the current situation, Satya Gupta adds, there are two types of companies that can help India’s Semiconductor Mission. First there are established companies like Micron, Intel, etc. Second, and more importantly, large Indian conglomerates.

“Recently, there have been some indications about Reliance Industries exploring investments in this area. A company like Reliance or Tata [group] with the deep experience of executing large projects, global reach, long investment mindset, financial muscle power, and their focus on digital technologies and customers will be a very potent recipe.”

Read More: Uttarakhand to Implement UCC; How It Will Impact Marriage, Divorce, Adoption, Inheritance Laws

One source of hope for India is the emergence of an electronics manufacturing ecosystem over the past decade. Playing to its strengths and taking advantage of countries’ desire to diversify their supply chain beyond China, India has managed to lure some of the biggest names—like Apple, Samsung, HP, Dell, and Lenovo—to set up assembly lines in India.

Taking a leaf out of that playbook perhaps, India has also been aggressive in pitching the country to semiconductor majors. From PM Modi to Ministers of MeitY Ashwini Vaishnaw and Chandrasekhar, they have all held multiple consultations with stakeholders to apprise them of the developments on the policy front. Besides, in the past two years, the government has addressed gaps in infrastructure. Sources at MeitY tell Business Today the government is evaluating some more proposals.

India will hope that these come through, and soon.