The foundation of the opposition was both religious and political, and rooted as much in the East India Company’s territories in India as in their home country.

In June 1793, William Carey, a shoemaker and teacher from Northamptonshire in England, along with John Thomas set sail for a special project in India. They were the first-ever English missionaries to arrive in the subcontinent, but their timing could not have been worse.

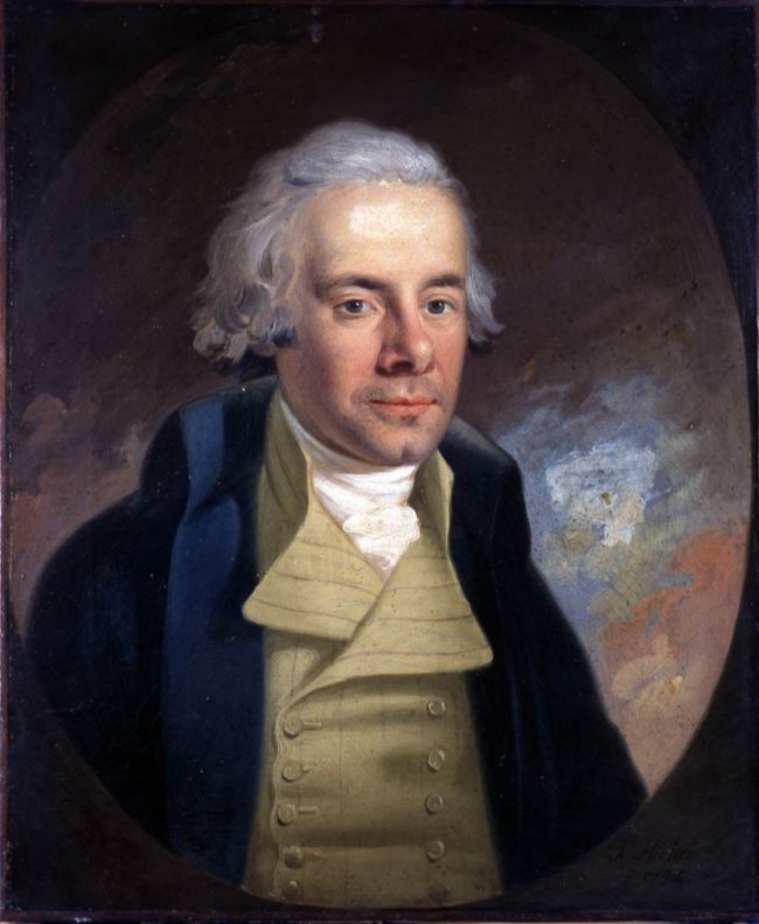

That same year, William Wilberforce, an evangelical member of the British Parliament, had proposed that the East India Company must finance missionary activities in its territories. The ‘Pious Clause’ as it was called was, however, defeated on the grounds that it was a financial and territorial risk to the Company. The Company’s Court of Directors’ standing order for the expulsion of all unlicensed British people arriving in India was renewed.

It was in this context that Carey and Thomas boarded the Danish ship Kon Princess Maria. Five weary months later, they reached the coast of Bengal, from where they traveled to Bandel, an old Portuguese settlement. Thus began a long missionary career that also set the stage for others to find the same calling.

By 1800 Carey and Thomas had settled in the Danish town of Serampore. During this period, however, right upto 1813 when the Charter Act was introduced, the Court of Directors, did everything in their power to make life difficult for the missionaries. For instance, they ordered all Europeans in India, not in the service of the Company, to take out certificates of residence and have bondsmen to stand surety.

The opposition of the East India Company towards missionary activities in India has been studied extensively but scholars often differ in their explanation of the motives. What is clear though is that the foundation of this row was both religious and political, and rooted as much in the EIC’s territories in India as in their home country.

Religious reform in England and fear of losing to the French

This was a period of substantial religious reform activities in England. The Protestant dissenters, such as the Lutherians and Puritans who had long been against the Church of England, were joined by several other denominations in the late 18th century. For instance, the Baptists, to which Carey and Thomas belonged, formed what was called the ‘new dissent’.

“According to an 1811 House of Lords report, the Church of England was on its way to becoming a minority religious establishment,” writes historian Karen Chancey in her article, ‘The Star in the East: The controversy over Christian missions in India’ (1998).

Anglicans were concerned about the effect of the dissenting groups on the official church. At the same time, the evangelicals within the Church were beginning to adopt a dissenting tone. They were interested in social and religious reform measures and in missions. It was in this context that Wilberforce proposed that the EIC foot the bill for missionary activities inside the empire. “The measure was defeated by the combined efforts of the Company, which objected on financial grounds, and Anglican leaders, who were more interested in combating the threat of the dissent at home than in proselytising abroad,” writes Chancey.

Another reason for the Company’s antagonism towards missionaries was the expanding territories of the EIC in the late 18th century. Between the 1790s and 1813, the Company’s territories in India had more than doubled. The largest acquisitions were made under the governor-generalship of Richard Wellesley who put significant censorship on the press and restricted freedom of movement of the Europeans. Such a move was justified on the grounds that it was necessary to control such Europeans who were not employed by the Company and were therefore not their responsibility. Carey and Thomas belonged to this category since neither did they carry Company permits while arriving in India, nor did they travel in a British ship.

However, the missionaries did have their supporters among Company officials, such as Claudius Buchanan, an evangelical who was appointed chaplain in Calcutta and Vice-Principal of the Fort William College. Buchanan lamented the lack of morality among Europeans and Indians. Among Europeans in Calcutta, he had observed in shock the excessive drinking and gambling and blamed it on the lack of sufficient ministry among the Company’s ranks. The moral state of Indians, he believed, was much worse and he wrote in horror about practices like female infanticide and Sati. He hoped that the work of the missionaries would dispel the vices in Indian society. In 1805, Buchanan published a memoir titled, ‘Memoir on the expediency of an eccelssiastical establishment for British India’ in which he argued for a formal Anglican presence in India to minister Europeans there.

Buchanan’s memoir sparked a public debate on whether or not the Company must support the work of the missionaries. But there was yet another factor bothering the British at this time: the French. By 1799, the impact and fears caused by the French Revolution and wars with the French began to be felt in India. The Company authorities were aware that if the missionaries caused disaffection among Indians, they might soon turn to the French.

The Vellore mutiny and the fear of triggering the wrath of Indians

On July 10, 1806 at the Vellore Fort where the family of Tipu Sultan was imprisoned, Indian sepoys crept up and murdered the European sentries. This was the first instance of a sepoy mutiny against the British, predating the 1857 revolt by almost half a century. Nearly 200 on the British side were killed or wounded.

The Vellore mutiny sent shock waves, both in India and Britain “Opponents of missionary activity seized on the mutiny as proof that their arguments that Indian religious prejudices were easily excited were only too true and that the greatest caution was needed in any interference with them,” writes Penelope Carson in his book, ‘The East India Company and Religion: 1698-1858’ (2012).

Lord William Bentick, who was the governor of Madras at that time, blamed the new dress regulations for the sepoys as the cause behind the mutiny. The new dress code forbade the use of caste and religious marks. This, in the opinion of Bentick, was seen by the sepoys as efforts at converting them to Christianity.

The anti-missionary lobby argued that in this situation, it would be dangerous on the part of the British government to allow missionary activity in India, especially when they were being conducted by ‘ill-educated and fanatical dissenters’.

Carson notes that a number of factors were cited to make the case that Indians believed the Company was intent on converting them to Christianity. “First, it was pointed out that three British missionary societies were operating in the Company’s territories: iterating, preaching and distributing thousands of tracts,” writes Carson. Secondly, proposals for printing the scriptures had appeared in the Madras Gazette shortly before the mutiny. Thirdly, the anti-missionary lobby argued that the sepoys would have known that a number of Evangelical chaplains had been sent to India in service of the Company a year before. All these were conjectures and the last point was highly unlikely, since Indian sepoys rarely would be able to differentiate between an Evangelical chaplain and a missionary.

Nonetheless, the mutiny did have its impact on the decisions taken by Company officials against missionary activities. The acting governor-general, George Barlow, immediately restricted missionary activities when news of the mutiny reached Bengal. In August 1806, the magistrate of Dinagepore (in present day Bangladesh), ordered two newly arrived Baptist missionaries back to the Danish enclave of Serampore. Two other newly arrived Baptist missionaries, John Charter and William Robinson, were ordered home.

The controversy was laid to rest, at least temporarily, by Lord Teignmouth, who was then a member of the Board of Control in the Company. He argued that none of the soldiers questioned after the mutiny had mentioned anything about the missionaries being a factor, and were definitely not aware of Buchanan’s call for expanding missionary activity in India.

The issue was put to vote in the Board of Control and the anti-missionary lobby lost. The fact that anti-missionary activity was detrimental to the Company was unconvincing given that the British Empire was almost free of its enemies at this point in time. Internally, rulers like the Marathas or Tipu Sultan had either been defeated or rendered harmless by treaty. Externally, the French had been defeated by the British in Egypt in 1801 and most French sympathisers had been removed from the subcontinent.

In the following years, Buchanan’s proposal for the establishment of a formal eccessiastical body in India gained popularity among British church goers. By 1813, the issue had become less of a religious one and more of a debate over whether and to what extent the Company ought to be kept free from the Crown’s authority. “The question was argued in pamphlets, in petitions to Parliament, and in debates in the Court of Proprietors and in Parliament,” writes Chancey.

Finally, when the Company’s charter was renewed through the Charter Act of 1813, it explicitly asserted the Crown’s sovereignty over British India. It also gave missionaries a free hand, and allowed them to preach and propagate their religion. By the 1820s and 30s, Protestant missionary activities in India had increased quite a bit, and they did their part in combatting social evils like female infanticide and Sati.

Further reading: