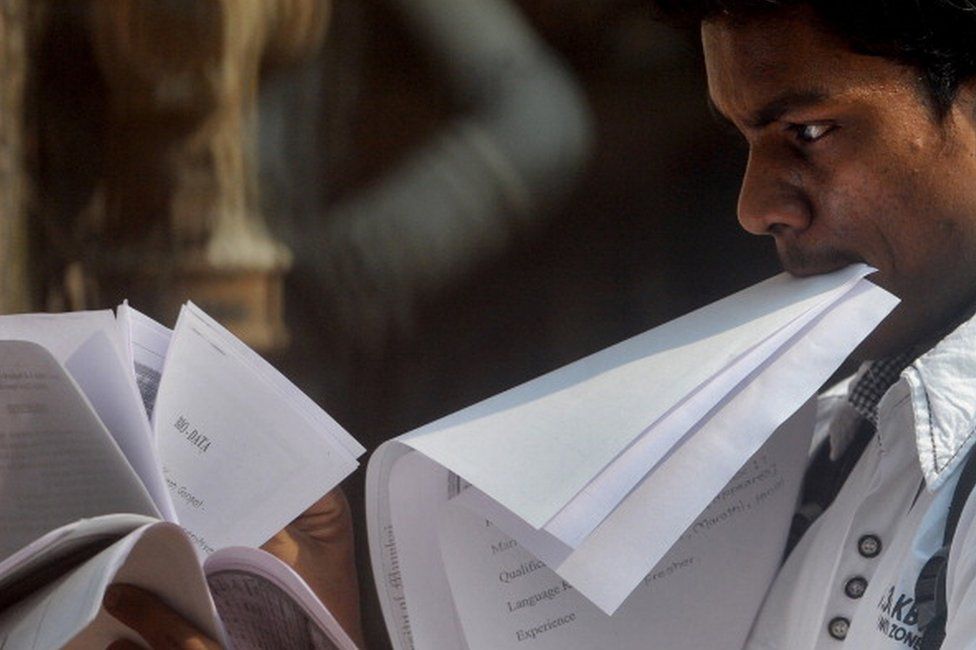

Last week, a law graduate in India applied for a job as a driver.

Jitendra Maurya was one of more than 10,000 jobless young people who turned up for interviews for 15 low-skilled government jobs in the central state of Madhya Pradesh. Many of them were overqualified – aspirants, according to one report, included post-graduates, engineers, MBAs and people like Mr Maurya, who is preparing for a judge’s exam.

“The situation is such that sometimes there is no money to buy books. So I thought I will get some work [here],” he told a news network.

Mr Maurya’s plight shines a light on the acute jobs crisis facing India. The pandemic battered Asia’s third-largest economy, which was already in the throes of a prolonged slowdown. It’s now seeing a rebound largely due to pent-up demand and increased government spending.

- India economy: Seven years of Modi in seven charts

But jobs are diminishing. India’s unemployment rate crept up to nearly 8% in December, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), an independent think tank. It was more than 7% in 2020 and for most of 2021.

“This is way higher than anything seen in India, at least over the last three decades, including the big [economic] crisis of 1991 [when the country did not have enough dollars to pay for imports],” Kaushik Basu, former chief economist of the World Bank, told me.

Most countries saw joblessness rise in 2020. But India’s rate exceeded most emerging economies like Bangladesh (5.3%), Mexico (4.7%) and Vietnam (2.3%), notes Prof Basu.

Even salaried jobs have shrunk, according to the CMIE. Part of this could be because firms have used the pandemic to trim their workforce and reduce costs. Studies by Azim Premji University show young workers – 15 to 23 years old – were hardest hit during the 2020 lockdown.

“There was a churn. We found that about half of those who had salaried work before the lockdown could not retain such work,” Amit Basole, an economist at the university, told me.

The pandemic is only partly responsible for the sharp decline in jobs, economists say.

“What has happened in India reflects the fact that policy is being made with little attention to the wellbeing of workers and small businesses, as we saw during the lockdown in 2020,” Prof Basu said.

For one, these dismal headline numbers don’t tell us the whole story about persistent joblessness in India.

The number of active job seekers in the working age population has fallen. The proportion of women, aged 15 and older, in the workforce is among the lowest in the world.

- Young bearing the brunt of sweeping job losses

But unemployment in India mainly refers to educated young people looking for jobs in the formal economy – although the informal economy employs 90% of the workforce and generates half the economic output.

“Unemployment is a luxury which the educated, relatively well-off can afford. Not the poor, unskilled or semi-skilled people,” said Radhicka Kapoor, a labour economist.

The more educated the person is, the more likely it is they’ll remain jobless and unwilling to take up a low-paying informal job. On the other hand, the poor who have little access to education are compelled to take up whatever work comes their way.

So, unemployment numbers don’t reveal much about the total supply of workers in the economy as a whole.

Three-quarters of India’s workforce is self employed and casual, with no social security benefits.

Only a little over 2% of the workforce have secure formal jobs with access to social security – a retirement savings scheme, health care, maternity benefits – and written contracts of more than three years. A paltry 9% have formal jobs with access to at least one social security source.

“The majority of India’s workforce is vulnerable and leads a precarious existence,” Dr Kapoor said.

Earnings are slim. Surveys show 45% of all salaried workers earn less than 9,750 rupees ($130; £96) a month. That’s less than 375 rupees a day, the minimum wage proposed in 2019 but later dropped.

One reason behind India’s endemic unemployment despite high growth is the country’s leapfrogging from a primarily farm economy to a booming services economy – in no other country of India’s size has growth been led by services and not manufacturing. India’s growth has been powered by high-end services like software and finance manned by highly skilled workers. There have been few manufacturing or factory jobs that can absorb a large number of unskilled or low-skilled workers.

- 1991 reforms: ‘A long distance call was like an endurance sport’

India’s joblessness is worrying because even as the country’s growth is restarting, the bottom segment is doing worse than in most other nations, Prof Basu says. He believes the government needs to control inflation, generate employment and support workers. Also, a “politics of polarisation and hate” during Mr Modi’s rule is “damaging trust, which is one of the most important underlying drivers of economic development”.

Mr Modi, who swept to power in 2014 promising jobs aplenty, is offering financial incentives to key industries and running an ambitious “Make in India” campaign to encourage local manufacturing. None of this has so far led to a manufacturing – and jobs – boom, in part due to depressed demand.

In the short term, many like Dr Basole feel India urgently needs cash transfers or an employment guarantee scheme for the bottom 20% of struggling households in cities to help them consume and pay back debt. In the long run, the challenge is to ensure that all workers have a basic minimum wage and social security.

“Until then we cannot have any meaningful reforms in jobs,” Dr Kapoor said.