Mr Singh, an accountant, says he paid 5,000 rupees (£48; $66) up front and borrowed an additional 35,000 rupees – a loan he claims was facilitated by Byju’s – to buy a two-year math and science programme for his son.

“A sales representative came to my home and asked my son all kinds of difficult questions which he couldn’t answer,” Mr Singh said. “We were completely demotivated after their visit.”

He told the BBC he felt shamed into buying the course. But he claims he didn’t get the services he was promised – including face-to-face coaching, and a counsellor who would call and update him on his son’s progress – and that after the initial months Byju’s stopped answering his calls.

Byju’s called his allegations “baseless and motivated” and told the BBC Mr Singh “was spoken to several times in the follow-up period”. They said they had a “no questions asked” 15-day refund policy for their product, if a student opts for learning material with an accompanying tablet, and an “anytime” refund policy for their services.

he company said Mr Singh asked for a refund two months after the product was shipped. But after the BBC brought Mr Singh’s case to their attention they gave him the refund he was after.

The BBC spoke to many parents who said the services they were promised – one-on-one tutoring and an assigned mentor to assess the child’s progress – never materialised. In at least three different cases, India’s consumer courts have ordered Byju’s to pay damages to customers in disputes related to refunds and deficiency of services.

Byju’s told the BBC that they had reached a settlement in these legal cases, and their grievance redressal rate was 98%.

But a BBC investigation based on interviews with former Byju employees and customers has revealed several allegations.

Disgruntled parents allege they were misled by sales agents. They said they were lured into contracts by agents who convinced them of an urgent need only to go incommunicado a few months after the sale, making it difficult to get a refund. Once a sale is done, agents would be “least bothered” to follow up, a former Byju’s employee said.

Former employees complained of “pushy managers”, claiming there was a high-pressure sales culture that emphasised aggressive targets. There are also hundreds of complaints in online consumer and employee forums against the company.

Byju’s denied using aggressive sales tactics and said “only if the student and parent sees value in our product and develop trust do they purchase it”. They added that their “employee culture does not permit any misbehaviour or bad behaviour towards parents” and that “all rigorous checks and balances are in place to prevent misuse and abuse”.

Founded by Byju Raveendran in 2011, Byju’s is funded by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and major private equity firms such as Tiger Global and General Atlantic.

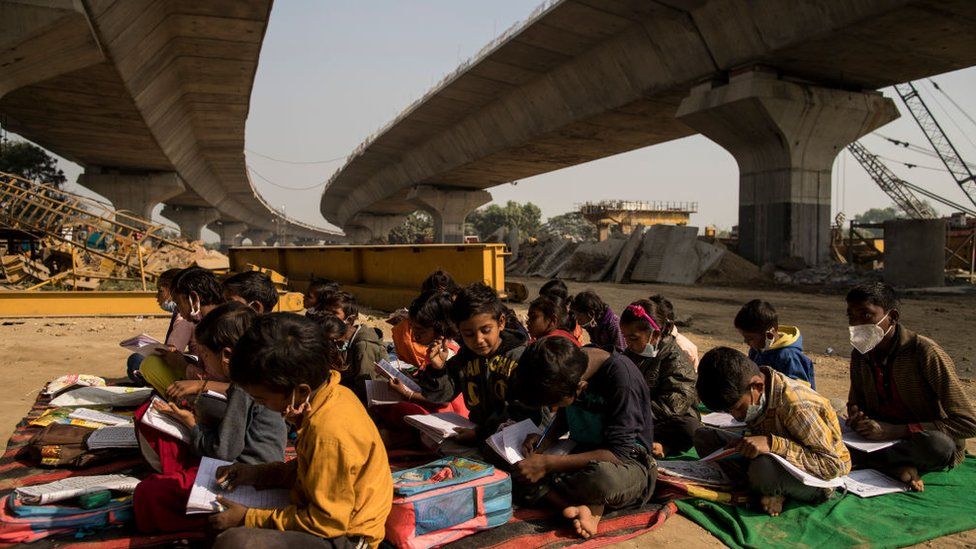

With schools being closed for more than a year-and-half, the pandemic forced millions of Indian students to turn to online classes. And the sudden switch made anxious parents like Mr Singh – who traditionally see education as an essential ticket to upward mobility – a crucial market for Byju’s.

So the firm’s ascent since the pandemic began has been nothing short of meteoric. It claims it added more than six million paying users, with a 85% renewal rate.

The BBC spoke to several students and parents who vouched for the quality of Byju’s learning content – in a country where rote learning is often the norm, Byju’s has been credited for deftly using technology to create immersive, engaging lessons. It also claims to have the industry’s highest net promoter score (NPS), which measures customer experience and predicts business growth.

Byju’s has raised more than $1bn since March 2020 and gone on an acquisition binge, mopping up a dozen competitors to become an umbrella holding company for firms offering everything from coding classes to coaching for competitive exams. It’s possibly the most visible brand on Indian TV, with Bollywood superstar Shah Rukh Khan driving its flashy ad campaign as brand ambassador.

But some education experts have questioned whether the company’s rapid growth is a result of hard sales tactics that have fed into parents’ insecurities, and added to their debt burden. Parents claim the tactics included incessant cold calls and sales pitches whose effect was to convince them that their child will be left behind if they don’t by a Byju’s product.

Given that even Byju’s basic courses start at around $50 – unaffordable to most Indians – the company often pushed its product irrespective of whether the child needed it or the family could afford it, a former employee said.

“It does not matter if he is a farmer, a rickshaw puller. The same product is sold for a range [of prices]. If we see that a parent cannot afford it, we charge them the lowest price in that range,” Nitish Roy, a former business development associate at Byju’s, told the BBC.

Byju’s said they have “different products at different price points based on customers’ needs and affordability” and do not change prices in “the manner suggested”. It also said sales executives have no control over pricing.

Several current and former employees also told the BBC they were often pushed to meet unrealistic targets. Two recorded telephone conversations which appear to show furious managers humiliating sales people for not meeting their targets surfaced online late last year and in January this year,

Byju’s told the BBC the conversations took place 18 months ago and it took necessary steps to rectify the situation, including terminating the contract of those managers.

In a statement to the BBC, Byju’s said “there is no room for abusive, offensive behaviour in our organisation. The affected employee in the case referred by you continues to remain with us and enjoys management’s confidence”.

But more than one employee told the BBC that the pressure to make a sale was so high that it took a toll on their mental health. One sales executive said he developed anxiety, and his blood pressure and sugar shot up during the year he worked at Byju’s.

Several employees said 12-15 hour work days were a regular feature of their job, and staff who couldn’t clock 120 minutes of “talk-time” with potential customers were marked absent, resulting in loss of pay for that day.

“That would happen to me at least twice a week. I’d have to make at least 200 calls a day to be able to hit the target,” a former employee said.

He added that the target was incredibly difficult to meet because he would be given few leads to chase and an average call would often last less than two minutes.

But Byju’s said it was incorrect to suggest that it “either docks salaries or marks people absent if they fail to hit the target in the first instance”.

“All organisations have rigorous but fair sales targets and Byju’s is no exception,” the firm said. They added that mindful of employees’ health and comfort, they offered a robust training programme.

“We have thousands of employees across our group companies and even in the case of a one-off incident, we immediately evaluate and take strict actions against mistreatment.”

But Mr Roy, who now teaches orphans in a school in Mumbai city, says he left Byju’s earlier this year after a two-month stint because he was deeply uncomfortable with how the company operated.

“It started as a noble concept, but has now become a revenue-generating machine,” he added.

Pradip Saha, co-founder of Morning Context, a media and research company that reports extensively on India’s start-ups says much of this “boils down to the pursuit of growth at a rapid pace”. He said this was not a problem peculiar to Byju’s, but the edtech sector as a whole.

Despite mounting criticism, he said, he doesn’t see drastic change around the corner.

“Most of these complaints are anecdotal. And only a handful of them find a platform, if at all. When you put these complaints against the revenue that these start-ups are generating, it becomes a no-brainer.”

But the clamour for regulation is growing.

Dr Aniruddha Malpani, a doctor, angel investor and vocal critic of Byju’s business model, told the BBC the time is rife for a Beijing-style crackdown on edtech start-ups in India. China recently mandated that online tutoring firms must turn not-for-profit.

The solution already exists, Dr Malpani believes. He says the Indian government should replicate the “Netflix model” to regulate the sector, referring to a monthly subscription model that has no minimum lock-in period.

“This would align interests immediately, because then, you make money by delighting your students on an ongoing basis.”

The Indian government is yet to step in – but it may soon need to as parental grievances rise. Dr. Malpani says he is preparing to petition the courts asking the government regulate the sector.

“You see all these headline numbers, with so many millions raised and the world’s most valuable ed-tech start up… All these are pointless vanity metrics,” Dr Malpani said.

“I think at some point we can’t afford to forget that education like health care is a public good.”